This is a dynamic analysis conducted on a malware sample (named locky.7z) provided during a class of mine. This writeup is an adaptation of the lab report I wrote for this class to note down what I learned and explore the malware sample.

To begin with, I downloaded the sample onto an airgapped system running Mandiant’s FLARE virtual machine. I extracted the sample from the 7z file to the desktop and started by investigating whether or not a packer had been used to obfuscate the code. To do so, I started by loading it into Detect it Easy and scanned the file, as shown below:

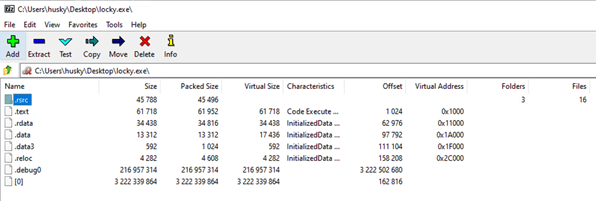

Examining the results, we can see that there are three sections identified as packed by DIE, though no obvious information about what packer might have been used. To attempt to go deeper, I ran the malware through Universal Extractor, which threw an error indicating that the malware might contain a 7z archive (annoying, but a vital piece of information in the puzzle). Moving over to 7zip, I opened the executable file and found the contents:

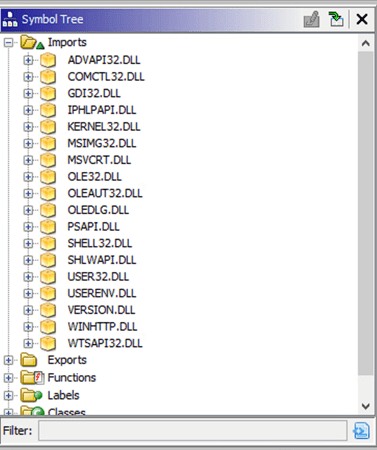

Taking the unpacked malware, I threw the contents into Ghidra to attempt to get a better idea of what it might do. Specifically, I took a look at the imports table to try and get an idea of what functions the sample was importing from Windows libraries. Below are the results: the malware imports the DLLs ADVAPI32, COMCTL32, GDI32, IPHLPAPI, KERNEL32, MSIMG32, MSVCRT, OLE32, OLEAUT32, OLEDLG, PSAPI, SHELL32, SHLWAPI, USER32, USERENV, VERSION, WINHTTP, and WTSAPI32.

Examining this list, there are a few libraries that immediately caught my attention, starting with WTSAPI32.dll, which handles Remote Desktop services for Windows. Expanding WTSAPI32, there are two functions imported: WTSEnumerateSessionsW and WTSFreeMemory. WTSEnumerateSessionsW is a built-in Windows function that retrieves a list of all the sessions on a Remote Desktop Session Host server, while WTSFreeMemory will free up memory allocated by a Remote Desktop Services function. The two of these functions imply that the malware is potentially interacting with Remote Desktop Services, either starting a session with the attacker or attempting to read and steal information for further exploitation or to find the potentially sensitive files related to existing sessions on the victim system. Given that none of the other functions are imported, I believe that this is attempting to find sensitive information either for other computers on the network or for sessions on the victim system itself.

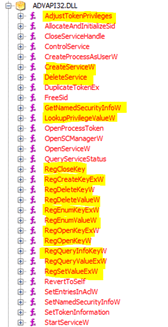

Next is ADVAPI32.dll, which is a library that provides security calls and functions relating to the Windows registry. This lends itself to doing major damage to the system. A variety of functions are imported from the DLL by the malware, most interestingly those that handle looking up security info, manipulating the registry, and creating or deleting services – all of which could potentially be used to damage the system and steal sensitive data.

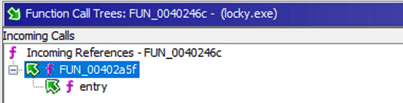

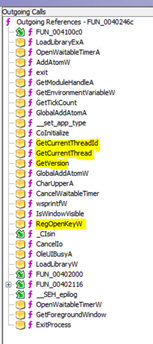

Continuing the analysis, I had a look over the functions that Ghidra had built out while decompiling the malware. There is one particular function, “FUN_0040246c”, that appears to contain the main functions of the malware. This function takes the output of “FUN_00402a5f”, itself started by the “entry” function, as shown below. The outgoing calls from this function (bottom picture) seem to handle examining the system the malware is running on (tGetCurrentThread, GetVersion, RegOpenKeyW etc.).

Based off the imports and functions in the malware, it is at least capable of reading, writing, and manipulating files, examining processes on the system, reading and modifying the registry, and accessing deep levels of system data – including looking into remote desktop sessions that the victim may be hosting. The access afforded by kernel and video-related DLLs (such as GDI32.dll) implies that the software is potentially capable of messaging the user or altering displayed information. Finally, the internet capabilities from WINHTTP.DLL implies that the malware is capable of accessing the internet, manipulating the user’s ability to access the internet, or at least monitoring the user’s internet activity.

This isn’t a complete examination, but I hope it was at least interesting to read along with my work!

Leave a comment